The Grammar Teacher the third story in Five Selves, Holland House Books, 2015.

Under my shirt, tucked somewhere between my skirt and my body, I smuggle something out. It may be a camisole I fold to the size of a cigarette pack, perhaps a small piece of tableware I would like to have; a couple of times I have even taken cosmetic creams which I could hardly hide under my arm, they almost fell out as I walked to the exit. First I look to see if the security guards are nearby. If the coast is clear I begin to walk slowly, in a casual manner, towards the exit, making sure to stop on the way to examine another small object so as not to arouse suspicion. About five steps from the door there is always a childish desire to run out, as if it is all a game and I am one step away from winning. In a moment I will cross the store’s wide exit doors and the stolen treasure will be mine. But it is here that self-control is needed: a slow and moderate step, one that doesn’t betray the wish to escape as quickly as possible.

Sometimes on the way out I have to give up, accept a loss, place the object somewhere and leave empty-handed. The security guards, however, are not inclined to suspect women like me. I often see them following groups of young girls, who hope that if they are caught they will be able to blame each other and the thief won’t be arrested. First they gather around the hangers, examining and inspecting, then they decide which garment they want; one of them tucks it into her handbag and together, laughing loudly, they walk slowly and leave the store. The security guards, mostly young and inexperienced men, can’t face a group of young women chatting and smiling on their way out. Once, a new guard on his first shift made a mistake and asked the girls where the bathing suit they were holding was. The bursts of laughter and the blunt remarks embarrassed him to tears and he swore he would never stop them again, even if he was absolutely sure they were stealing from the store.

But no one suspects me. I am a woman of somber, respectable appearance. My black hair is simply cut and pulled up in a plain rubber band, my shirts are always tucked in to dark, straight skirts; I carry a gray handbag, I am slightly over-weight but exuding vitality; my entire appearance, aside from my pug nose, speaks of decency and good manners. When I enter the store no one could possibly guess my intentions. Saleswomen treat me kindly, obviously a customer like me must be satisfied; clearly I don’t intend to waste my time walking aimlessly between the counters. I pace quickly, as if I were in a hurry to carry out a busy daily routine. There is always a diligent saleswoman who will suggest garments on sale, her instincts leading her to believe I want to make the most of my money. I smile kindly. I am sorry that although she is trying so hard, I refuse politely and keep walking around the store. After she gives up and immerses herself in conversation with other faded and tired saleswomen I advance towards the object I am about to take.

It’s been several months now that I have been wandering through stores. I covet things and take them secretly. I never imagined that circumstances would make me do this. I used to think that a person growing up in a stable and respectable family like mine could never end up stealing. I felt I could see my life stretching ahead, and every stage would follow the previous one clearly and naturally. I never imagined I would walk out of a department store with a shirt hidden in my pocket, an overwhelming happiness at not having being caught taking me over completely.

I used to be a grammar teacher. I always knew I would be a teacher. As a child I really liked school; I always answered questions in class and at home correctly, simply, and clearly. The teachers used to comment on my ability to explain everything in a mature and responsible way. I was hard-working and tidy, my books and notebooks were always placed neatly in my backpack; more than once a teacher who lost her notes would ask to take a look at what I had written. In full, rounded handwriting, which never exceeded the top or the bottom of the line, without any decorations or scribbling created by boredom, I wrote down everything that was said in class. I detested children who interrupted. Next to me sat a fat, stupid girl with almond eyes who giggled constantly; if I could have, I would have expelled her from school.

In high school I invested all my energy in learning. My homework was always ready and I never forgot anything at home. Every evening the backpack was placed buckled beside the bed, ready for the next day. My parents were very proud of my achievements, but a couple of times my mother suggested that I spend some time with friends and ease up on the studying. I, however, felt I was standing in a sort of confined zone, whose boundaries must never be crossed. I found it hard to explain, the boys and girls around me seemed to me distant, almost strange, living according to a different inner mechanism, following a tune I never heard. Yet in spite of the isolation from my peers, except for one girl friend, I felt I had a special place in class that couldn’t be taken by anyone else.

Of course there were unpleasant moments: next to me sat a slender girl with wide open blue eyes encircled by a stroke of black paintbrush, ignoring lustful looks and amusing remarks and looking at me with a mixture of wonder and contempt. I would rather have sat alone; the teacher who made her sit next to me said loudly that she was hoping I would encourage her to study more seriously. She merely watched me distantly, wondering what she could possibly learn from me. There were also a couple of boys who used to take my notebooks before class and copy homework, laughing and grabbing the notebook before I agreed that they take it. At first I didn’t dare refuse. Later I used to pretend I didn’t hear them asking.

But all these embarrassments evaporated when I got the highest grade in class, or when teachers openly praised me. Then I felt everyone acknowledged that my presence in class was worthwhile and justified. Endless hours of studying boiled down to a couple of moments of explicit joy; but they supported me in days in which I was entirely steeped in solving math problems or summarizing history chapters.

Thus, it was only natural that I decided to become a teacher. When I came to my first job interview at a comprehensive school I was excited and somewhat confused. I put on a dark gray skirt and a straight shirt with small buttons, my appearance conveying integrity and earnestness. As I waited behind the closed door of the teachers’ room, I saw my reflection in a window—a young woman with a rounded figure, a solemn countenance, squinting in order to detect any invisible flaw that might impede her. Suddenly I saw that a button in my shirt was unfastened; my fingers were shivering as I fastened it, before I was asked to come in. The principal greeted me with a forced smile and asked me to follow him. On the way to his room he ordered the janitor to fix the school’s gate, reproached a young teacher for being late for class, and gently rebuked the secretary for not preparing a list of required equipment. When we got to his room he left the door open, and sat down without inviting me to sit. Out of embarrassment I collapsed into one of the chairs, and then he lifted his eyes and looked at me as if seeing me for the first time. He looked at my CV very briefly, as if it was an irksome duty that must be completed, as though I was a student presenting last year’s report. Then he asked me about my experience. His expression betrayed neither sympathy nor reservation. Finally, considering every word, he said a teacher was going to leave the school soon, but he was not sure when exactly she would leave or whether a new teacher would be hired to replace her. When she did leave, the school would contact me.

While I was waiting at the bus stop outside the school, a young girl sat next to me, her body soft and adolescent, her face full of acne, carrying a faded, graceless backpack. As the school bell rang, she turned her head backward and looked with hostility at the schoolyard, almost with revulsion. Then she let her hair out of the thin rubber band, twirled it around her short fingers several times and tied it behind her head again, without leaving a single hair to sway in the light wind.

At the next job interview the principal was much nicer. An elderly woman, her face made up not to beautify herself but merely to convey an effort of embellishment. She suggested that I give a grammar class and she would observe my teaching. Of course I consented, but her testing me without letting me know in advance and allowing me to prepare myself made me feel I had failed before I even started. My explanations were vague, I made serious mistakes about issues I knew perfectly well, and towards the end of the class I was confused by a simple question from one of the students. When the bell rang I left the class in a hurry, without even asking the principal if she would consider hiring me.

Finally I got a job at an old, respectable high school with students from well-established families. During the first days I was extremely embarrassed; I felt as if I was a student that was being allowed to substitute for a teacher. In class I shivered a bit, but the students were full of the excitement of the beginning of the school year and didn’t notice it. I made several mistakes reading the names, and laughter and gloating erupted in the class. But slowly silence came, the whispers and broken words were hushed, and my voice was heard, stable and clear.

The large, well-lit teachers’ room was a hive of activity. The huge windows were wide open and the windowsill packed with textbooks and workbooks. Teachers who hadn’t met during the summer break greeted each other loudly, almost shouting. Calls were heard from all corners of the room, a nasty remark about a teacher who had gained weight during the summer, a warm embrace to another teacher who had just gotten married. Some of the male teachers, a small minority among the many women, sat in their armchairs next to the wall and gazed with amusement at their noisy colleagues. A short while before the bell rang the principal entered the room. In spite of his solemn expression, his eyes betrayed a light smile. Due to a stroke half of his face was motionless; as he spoke he filtered the words, orderly and disciplined, never leaving an unfinished sentence or allowing a slang word to creep in. I was told he never engages in idle talk with the teachers, but on the first day of school his face assumes a unique expression resembling a smile, a twitch that could develop into a fully contented countenance and that might even have a touch of humor.

Embarrassed, I looked for a place to sit. At the end of the room, in a shadowy corner, some seats were vacant. I crossed the room cautiously, ignoring the loud voices, and sat on a plain wooden chair beneath the window. The hustle and bustle in the room, the cries, sometimes harsh and graceless, created a sense of disappointment. This is not how I imagined my first day as a teacher; everything about the teachers’ room seemed vulgar, lacking the refinement I was expecting to find. Two teachers sat next to me, speaking loudly. The older one was heavily made up, looking more like a sales assistant than a teacher; the younger had short light hair, her dress was plain, almost sloppy, and her strong voice echoed in the room; she burst into roaring laughter and clapped her hands. I sat there, staring at the teachers around me and wondering what went wrong. After a couple of minutes the school secretary came and asked me to fill out some forms. While I was engaged in the details the school bell rang, and all the commotion moved towards the door, fading gradually until all that was heard were thin, quiet voices from the other side of the room and the echoing voices of students playing in the schoolyard.

In the following lessons I managed to establish my straight, moderate voice in the classroom. The students looked at me with a mixture of respect and reservation. The unrestrained bursts of laughter were gone. I outlined the curriculum for the entire year and explained what assignments would be required for each class. I described the exams that would take place during the year. And so the process of studying began, orderly and structured, every class the logical consequence of the previous one. The entire year was spread before them, its limits well set and clearly divided. The distant gaze ahead created a peaceful and pleasant atmosphere in class, which only a couple of moments earlier had been full of a nervous, anxious murmur.

After a few weeks I made friends with a couple of teachers. An elderly lady with a thin, girlish figure and a pointed face used to sit next to me in the teachers’ room. She was a biology teacher, constantly complaining about the students: they don’t do their homework, they chatter in class, they are indifferent to the material, the boys and girls lack a fundamental curiosity, a desire for knowledge. She makes an effort to prepare the classes, carefully planning every lesson, but all in vain. Her graceless face stretches even further as she becomes absorbed in this monologue, a long speech with question marks, which she hastily replaces with exclamation marks. In fact, there was no conversation; I sat next to her and she muttered endless complaints. A literature teacher joined us, a woman with a somewhat sad face, who was nearly always checking homework in the teachers’ room. She gave endless assignments and read them with a grave expression, as if in one of them the solution to a riddle was concealed. She placed the assignments on the table, a pile of papers, some tidy some wrinkled, written in distorted handwriting, meticulously read them and wrote notes in red ink in the margins—though she had plenty of notes she never exceeded the margins. Finally she placed the papers in a stack, inserted them into a big envelope, and folded the top flap inwards. Then she lifted her brown eyes and looked sadly at the teachers’ room, desperate and proud, asking for assurance that she is indeed an extremely devoted teacher.

I also used to check the students’ assignments rigorously and fastidiously; I thought homework involved an element of imposing discipline, it was an exercise to tame one’s cravings, devoting oneself to a useful but unpleasant activity. Therefore I was very strict when it came to setting assignments. I detested students who didn’t prepare their homework; I thought they had a fault that must be corrected, a flaw containing a seed of peril.

After a couple of months everyone knew I was a diligent, committed, and punctilious teacher; true, some said that I was too rigid, I tended to concentrate on every word and to overlook the general context, that perhaps I neglect the personality of the student and ascribe too much importance to test scores. One teacher even suggested that my huge effort conceals a void in my personal life. Had I been married and a mother I wouldn’t have spent so much time reading assignments; but all these remarks were insignificant and negligible in comparison to the many compliments I received. The principal, who never joked with the teachers, would pass by me with his twitch that resembled a smile and a nod, and several times he even praised me explicitly. Some teachers openly disapproved of me, as though they considered me a traitor, betraying a common struggle to decrease duties. Others wished to befriend me, sometimes even asking for my advice on assignments and tests.

By the end of the school year everyone acknowledged my special place in school. The brown, faded armchair in the teachers’ room was always reserved for me, and even older teachers moved away when I approached it. The students knew I was highly esteemed, and some parents asked to meet me; they would begin by inquiring about their son or daughter but quickly the conversation turned to focus on me, hoping that the affinity between us might prove helpful in future crises. Whenever I entered the classroom the commotion and giggling died down immediately, and I walked at a moderate pace to the teacher’s desk. First I would place my books on it, then take out my notebook and turn to the board to write the subject of the day’s class.

My gestures in front of the class were slow and confident, I was never hasty. I erased the board with long movements, not stopping to read it but without any hurry; only when the board was completely clean did I begin writing the subject of the lesson in full, rounded letters, distinct but identical in size. Finally I turned to the students, looking at them gravely, and asked in a low voice who had prepared their homework.

Most of them watched me with awe. Sometimes I felt they could see the pupil that I used to be, a classmate standing in front of them whose sole advantage is that she prepared the material in advance. Yet it was these moments that made me feel my superiority, since even if I had been a student sitting in the first row and writing down every word, I definitely would have been the best in class. Some of them probably would have mocked me, but no one could take away the hint of a smile, subtle but apparent, as I looked around when on my desk there was an A+ exam, marked in red ink.

Once in a while there were unruly students who refused to accept my authority. In one class, a boy sitting next to the window kept staring at the schoolyard throughout the lesson. At first I decided not to say anything though I detested the way he ignored the lesson, like an explicit statement that it would be better to look outside than to pay attention to class. I thought it would be wise to leave him alone. But once in a while he stopped gazing out at the yard, and out of sheer boredom looked at me in a conceited, scornful manner, as if I were the student and he the teacher. I could hardly conceal my embarrassment; I turned immediately to the board, my shoulders rounded and my body shrinking into itself. With broken movements I began writing lengthy lines, so my blushing face could be hidden and the transparent tear would disappear by itself.

Against my better judgment, I was distressed every time I taught this class, as if a latent, obscure danger was materializing, even if momentarily, between the straight wooden chairs and the bright desks, etched with endless diagonal lines. Even before I entered the class I could envisage his beautiful face, decorated with blond curls, green eyes surrounded by almost white eyelashes, always looking into the distance to the school yard and beyond it. Sometimes he would squint, gazing outwards but looking as if steeped in a dream. Before every class I wavered, considering what I should do; sometimes I was determined to reproach him but I never dared to do so, I was afraid I would look silly: you can’t be angry at a student only because he is smiling. Thus I chose to ignore him.

But once, as a girl asked that I repeat an explanation, he burst into loud laughter. His striking beauty prevented others from rebuking him, and the miserable girl sat humiliated and blushing. I heard my voice, loud and harsh, in admonition, speaking of a student’s right to get an additional explanation and of the obligation not to embarrass a classmate, but I was horror-stricken. I thought the other students would join in his cheerfulness. In a moment the entire class would be in stitches, the disgraced girl would burst into tears, which would create further joy, more vulgar this time, and my voice would be swallowed in a stream of giggling and cries, the endless gaudy prattle of teenagers.

The handsome boy looked at me with contempt, listening to my reproach and smiling, sitting comfortably in his chair and stretching his legs forward, wondering what his punishment would be. Finally I asked him to leave the class. He sniggered, got up and slowly walked out, as though he had heard that he won a prize and he was going to collect it. When he left the classroom I was relieved. For a moment I feared I had sighed out loud, but as I saw the students returning to their books and notebooks, and the girl still expecting an explanation, I rebuked myself for being so scared: everybody knows I am such a gifted teacher, the fear that my voice won’t be heard in class is preposterous, even childish. Only the bell ringing halted the long, fully elaborated and well-reasoned answer to the girl’s question.

My parents were very proud of my success. Time and again they inquired how the classes are conducted, whether the students are obedient, what do I teach, how the other teachers like me. In spite of my embarrassment I told them about my success; they sat quietly, absorbing every word, never stopping my fluent speech, but apparently accumulating questions to be asked when I was finished. My father tried to follow the material; he always had remarks that were intended to illustrate how well he knew grammar. My mother was focused on the mundane aspects of school life, her questions always revealing a concern, an anxiety about the future: aren’t the other teachers jealous of me? Perhaps they would try to diminish my achievements? She heard of successful people who had failed because of the envy of colleagues. I should be careful not to disagree with senior teachers, try not to emphasize how well I am doing, and prepare everything in advance so no one would complain. So she immersed herself gradually in the troubles that could emerge any moment, struggling with obscure enemies that for her were so real. She lowered her gaze, her voice became somewhat whiny, and it was apparent she could visualize all these dangers that must be avoided; she was about to burst into tears, since in an instant I would be shamefully expelled from school.

Even though I knew every conversation would end this way and that my entire success, which initially had been so pleasant, would metamorphose into a danger that might break out at any time, each time a deep anger was awakened in me, spreading and filling every corner. My mother tried to conceal her anxiety in the recounting of how well I was doing: it was because I was so successful I should be watchful. But I heard the profound doubt in her words, a feeling that my many achievements, which to me seemed so solid, the result of talent and hard work, could disappear in an instant due to dark, obscure forces she failed to understand.

On the last day of the school year a slightly wild spirit prevailed in the teachers’ room: cries were heard everywhere, a pile of papers for recycling dropped on the floor and spread all over the room, dirty glasses were left on the tables, and one teacher told a dirty joke out loud. The giggling didn’t cease even when the principal entered the room. My two friends seemed alert, as if at the end of the day the invisible tie chaining them to this room—normally subordinated to strict, unequivocal rules but now touched by chaos—would be undone. As the bell heralded the end of the year both teachers and students rushed outside, impatient and nervous, barely stopping themselves from racing to the school doors as they opened with a rasping squeak.

I also stepped outside; already in the corridor, amidst the tumult of the students, among the backpacks rubbing against my arms on their way to the gate, I felt a gloomy spirit overcoming me. I planned to take advantage of the day to do some shopping and pay bills, but as I stood outside the school I felt such a deep distress that I decided to rush home. My bag, normally full of books and assignments, was annoyingly light and insubstantial. I walked away from school, marching briskly to the bus stop; all of a sudden I decided to return. I reproached myself for escaping from school, for joining the run to the gate without making sure that my stuff was safely locked away. I turned back and entered the building, which was by now completely empty except for faint voices coming from the upper floor. I walked slowly along the corridor towards the teachers’ room, finding it hard to accept the silence. An annoying thought crossed my mind: now the school resembles a market without any merchants; the food stands are untouched, full and seductive, but customers and vendors are all gone. I entered the teachers’ room and went to my locker. But next to the locker I saw a small wrinkled piece of paper on the floor, torn from a full page, written in a rounded handwriting. I picked it up and read: I thought about what you said and have reached the conclusion that you were right, there is no knowing what she will do, you had better watch out…

I dropped the paper, tossed my books into my bag, and ran in panic to the entrance; once again I saw the familiar pictures on the wall, the sports trophies, and the announcement of an end-of–the-year party, but I ran, gasping and breathless, in order to exit the school gate as quickly as possible.

During the summer I met Matan, my future husband. He introduced himself: a computer engineer in a developing company. He looked like a hard-working, ambitious man, determined to invest most of his time and talent in his job. When I saw him for the first time I could hardly conceal a smile. He had on a ribbed shirt, ironed and tight, tucked into pants with a laundry scent. When the shirt became slightly stained by the ice cream we were eating, he looked at me deeply embarrassed, as if he had failed to conceal a shameful flaw. Immediately he asked where I worked, and when I told him I was a teacher I saw content in his eyes, though he tried to disguise it. He asked me why I chose this profession. My explanations, about a desire to educate young people, to teach them the right habits, were loose, almost misleading. Finally I simply admitted that it was a natural choice, I had never considered any other occupation; my childhood and adolescent experience had made me become a teacher. Even though I saw he was relaxed and feeling at ease, I kept describing how well I was doing and added that in the coming years I might attempt to be appointed head grammar teacher in school.

Our wedding was attended not only by the principal and several teachers but also by the heads of the computer company employing Matan. The president, a chubby old man with hair dyed black, kissed me gracefully. He embraced Matan, and as he was holding him in his curved arm he turned to me and said in a pleasant, cordial manner that I should remember that we are family, and that from now on I am part of it too, and added that I should feel free to approach him with any problem or concern at any time. In the confusion of the wedding I didn’t pay attention to these words; but in the following days I was often bewildered by what he had said, inviting and uninhibited, moving me from the office to the warm bosom of the family, as if the gap between superior and subordinates didn’t exist. When I told my mother about it she looked at me, distant and absorbed in thoughts, and then asked me how long Matan had been working in this company. My father, overhearing the conversation from the next room, burst angrily into the kitchen. He was proud of Matan and thought he was a gifted, successful husband, and in no way was he willing to accept any doubt regarding the future flourishing career of his son-in-law. He reproached my mother and said he didn’t understand why she has to doubt everything; apparently the president really felt that Matan and I are part of the company’s family, and no wedding greeting could have been more appropriate and touching.

At the end of the summer I returned to school. I found the hubbub of the students pleasant, I walked along the corridors, pretending to look for someone just so I could listen to the calls and giggles, to smell the odor of teenagers, and to see how they walked into class with joy and not with desperation.

As always, the first class was devoted to a description of the curriculum for the entire year. I wrote on the board the subjects that would be taught, how many classes would be devoted to each subject, and what the required assignments would be. I was careful to explain the value of homework, how an extra revision of the material deepens our knowledge and, most of all, that learning habits are the foundation on which human knowledge is constructed. To create a certain connection with the students I admitted that youngsters of their age are normally preoccupied with things other than homework—words that generated pleasant smiles in the classroom—but still they must understand that discipline is a vital instrument for success in any field, and only a constant and structured effort would lead to achievements. This is the reason, I added, that I ascribe so much importance to homework and why in each class I would check if they were prepared properly.

My lessons were conducted in perfect order; the classes were quiet, with a touch of tension. The material was presented in a clear and simple way; therefore the students understood it very well. In exams at the school, my classes always got the highest scores for each grade. The principal pointed this out in the teachers’ monthly journal, and added his congratulations. My two friends were somewhat surprised, though everyone knew I was an esteemed teacher. The biology teacher, her face gloomy, said that apparently the students were more interested in grammar than in biology, and no wonder, they would use it in real life whereas biology would remain nothing more than a part of their general knowledge. The literature teacher looked at me sadly, trying to compliment me, but her gaze betrayed an inarticulate complaint.

My excellent reputation made students who refused to study look unruly or lazy. Some were angry at my fastidiousness, at the way I emphasized that assignments must be fully completed. In one class I encountered a slim girl with honey-colored hair almost down to her waist, who never prepared her homework. Whenever I reprimanded her she said nothing, blushing and looking at me with a penetrating look, full of wonder, as if she couldn’t understand why I insisted on creating such obstacles. Since her manner lacked any impertinence or insolence, I found it hard to enforce my way. Whatever I did was in vain: every time she was asked, she blushed and answered she hadn’t prepared her homework.

I don’t know why, I simply couldn’t accept the way she ignored any threat or punishment, acting as if school was a remote hotel she happened to be visiting where for some strange reason the manager of the hotel insisted that she clean her room. I decided to talk to her in private, without her classmates watching her in anticipation, alert to see how she would answer my question. As we entered a side room at school, she seemed embarrassed and shy. She stood motionless and waited for me to sit down, her face flushed but looking at me with concentration. I began by saying I don’t want to hurt her, on the contrary, I like her very much and I see she is an intelligent, talented girl, but she won’t meet the school’s requirement if she doesn’t practice at home. I added an explanation of the importance of constant perseverance, a striving not limited to a single achievement, brilliant as it might be, but to continuous progress, which is the only way to achieve anything substantial.

She looked at me with her huge eyes, making no attempt to refute my arguments or answer me. For a moment I thought she didn’t hear me, but immediately I reproached myself, this is a silly thought, clearly she is listening but she doesn’t respond. After minutes of explanations, which seemed extremely long due to her continuing silence, I decided to demand an explanation of her.

If the meeting had taken place today I think I would have burst into tears; perhaps I would even have embraced her and kissed her cheek when I heard her answer; but at that time she provoked a latent anger, a fury I didn’t know existed within me. Very simply, without any pretense, she said there is no need for that since once she graduated from high school she intended to move to a secluded village in the Galilee and live a plain, rural life, devoid of any professional ambition, and her most ardent wish was to sit on the porch and watch the view, especially during the evening hours, since the light is so soft and pleasant then.

When I answered her I realized my back was arched and my hands were joined fiercely. My voice sounded metallic, I used pompous language, words I would normally avoid. I spoke about duties everyone has, man’s responsibility to his society, I even said something about the moral implications of our actions. Though I knew I was using vague, empty clichés, I had no intention of stopping. Anger filled me, like a strange bubbling, as if my inner organs were disarranged and the order within my body was being violated; the wrath wasn’t directed outwards but it was merely pushing every organ away. Finally I was silent, and she looked at me with eyes full of wisdom, as if she was sharing my pain due to a misfortune or loss. Then I added that if she didn’t change her habits she wouldn’t be permitted to participate in the class, and at the end of the year she wouldn’t be allowed to continue to the next grade. She looked at me surprised, her face reddening and in her eyes a film of tears. In spite of the harsh threat she tried to understand the source of my arbitrary decision, but I added nothing and left.

One Saturday we dined at my parents’ place. The table was covered with an embroidered tablecloth with a delicate flower print. My mother decided to use the beautiful porcelain dishes, reserved for festive dinners. Next to every plate was a matching napkin, and beautiful glasses, long and oval, stood at a perfect distance from the plates. All the lights were on, reflected in the large glass bowls at the center of the table, and the room, that normally looked ordinary and even sloppy, was now dignified and inviting.

My father questioned Matan about his work. He never got tired of listening to stories about the computer company. He remembered every piece of gossip about junior employees and memorized any information on the senior staff. Matan began telling my father about a quarrel that had taken place at the office: the manager was angry at a young engineer who was negligent in his work and went home early in the evening, leaving on his desk e-mails that should have been answered instantly. The young engineer pulled his long hair behind his head, removed his glasses and put them on the desk, and replied that though he cares dearly about his work he refuses to be enslaved by it, and even if he doesn’t complete all the tasks by the end of the day, he will hurry home to be with his children.

Matan and my father disapproved of the insolent reply of the young engineer; my father noted, smiling, that perhaps he is not that smart, and Matan replied with a blink of agreement. My father said that you can’t just leave everything and walk away at five o’clock; one has a responsibility to the company, which may lose valuable contracts if the engineers don’t stay on schedule. Matan added that in order to work at a computer company and to achieve certain goals, one has to be consistent over time. Everyone thinks that computer guys succeed due to one brilliant idea, but the truth is that success is the result of constant hard work, and sometimes it takes years to execute an idea that was born almost randomly, in an idle conversation.

To support his point I told them about the student who never prepares homework and my conversation with her. As I concluded, I saw my mother putting down the boiling soup pot on the table, and staring at me. She seemed surprised, perhaps by my determined arguments, or maybe by my explicit threats; but her gaze revealed no satisfaction. Her thick eyebrows curved, she looked down at the table and began pouring soup into the small bowls. Matan and my father, unlike her, listened carefully to the details of the story, and as I concluded they began speculating on the student—maybe she quarrels with her parents, maybe it is an unstable family, perhaps her parents are uneducated and don’t know she is not preparing homework, perhaps she lies to them. I was forced to admit I don’t know anything about her family, but obviously she can’t go on like this, it’s clear, she understands it very well.

My mother seemed very disturbed by my story. In a low voice, as if a stranger was speaking from within her, she asked whether it was possible that the girl was telling the truth, that she indeed intends to move to a farm in the Galilee and therefore she is indifferent to success at school. Matan only smiled slightly, suffocating a giggle out of politeness, and after a couple of moments asked if he could have some more of my mother’s wonderful chicken which today, as always, was juicy and tasty. She gave him some more chicken, adding baked potatoes, and smiled at him aloofly, in her eyes a touch of ridicule, not to say contempt.

As we left, Matan hugged me warmly and complimented the way I had spoken with the student. He apologized—he didn’t want to say it in front of my mother, but sometimes she doesn’t understand what it is all about. He, however, is very proud of me, he wishes all the teachers would act like me. Gently he ran his hand through my hair, carefully, as if he had just found out how precious I was, and now there was a double need to take care of me.

Towards the end of the year national assessment tests to evaluate the students’ achievements took place. A gloomy spirit took over the school. The teachers were inclined to speak less in the teachers’ room, as if every moment should be devoted to preparing for the exams. In the many teachers’ meetings that took place in the evening hours, various suggestions were raised as to how to improve the scores. At first everyone sat next to a clean, tidy table, with plates full of cakes, juice bottles standing in two rows at its ends. But during the meeting, often prolonged into the night, pieces of cake dropped on the table, spreading crumbs which mixed with the sheets of paper scattered all around; disposable plastic cups fell on their side, rolling on their stomachs as the last drops of juice dripped on the table. The colorful napkins that the secretary bought were scattered all around, wrinkled and torn, hiding food residue in their folds, and some even fell to the floor and were left there untouched. The bottles passed from hand to hand, one accidently slipped on the table and left a golden puddle, which dripped to the floor. The secretary rushed to clean the syrupy fluid, but annoyingly it refused to be absorbed by the damp mop, and drops were smeared all over the table, leaving a trail of napkins dipped in sweet, sticky juice.

I sat there self-absorbed, holding my cup. My skirt remained straight and tight, free of crumbs. I never said a word, the agitation around the table was strange to me; I knew with full certainty that my students’ scores would be excellent. Months of organized, structured work would no doubt bear worthy fruits.

When the results of the tests were posted I smiled shyly. On the bulletin board in the teachers’ room they were arranged according to class and teacher. As I saw the papers hanging on the board I was a bit anxious, but a quick glance revealed that the scores of my classes were extremely high, and in one class they were even the highest in the country. A couple of teachers complimented me, but I smiled and looked down modestly, my countenance conveying humility. As the bell rang, I walked slowly to the classroom.

A couple of minutes after the beginning of the class a knock was heard at the door, and immediately it opened with a squeak. At the entrance stood the principal, and next to him was a woman of about my age, dressed very elegantly, her face made up and her light straight hair well-coiffed. As they entered the room the principal gestured that I should continue with my work. They stood in the corner, next to the wall, whispering and looking at me and at the students. The principal smiled at her; it was like a twitch of pain. There was something strange in his expression, a hint of a weakness he had never exposed. The woman moved her head in agreement, her hair moving forward and backward, and then, in a casual manner, she stretched one foot forward and leaned it on the thin, high heel of a red, shining sandal.

During class I wondered who she might be; probably a supervisor from the Ministry of Education who had come to watch a lesson due to the high scores of this class in the national assessments. Then I thought she might be a member of one of the many delegations that often visited the school. Dressed in an elegant shirt tucked in a straight, flattering skirt, her hair perfectly styled, by her appearance it was evident she was not a member of the staff. As I was asking the students questions and they replied, she laughed quietly with the principal, and then they both turned and left the class. I don’t know why, but I felt angry. Normally I was indifferent to visitors in the classroom, I perceived them as a necessity that couldn’t be avoided. But something about the posture of this woman, her cold look, the foot in the red shining sandal that she stretched gracefully forward, made me seethe with rage. As the bell rang I quickly collected my stuff and hastened to the teachers’ room, wishing to tell my friends about the annoying visit.

But as I entered the room I ran into the principal and the visitor. With a straight face he signaled me to come, and as I approached them he introduced her: a new grammar teacher, she came from a very prestigious school, and now we were extremely fortunate, so he said, that she had agreed to be part of our school. The teacher shook my hand coldly, examining me with a disengaged curiosity, while I stood before her discomforted and shy, wondering why the school needed another grammar teacher. The principal added that we should meet and discuss the teaching materials, looking at me indifferently and then smiling at her. She nodded, her hair bouncing back and forth, thanked him abruptly, and without waiting for his response turned around and left the teachers’ room. The principal’s gaze followed her and as she exited the room he muttered something about how we should decide together about the requirements, and then gave another vague sentence regarding fruitful cooperation between the two of us; his black eyes were wide open but he seemed like a blind man watching shadows and trying to make sense of them.

As I dropped into the armchair in the corner of the room I heard the word ‘cooperation’ over and over again. A dark, gloomy cloud began to take form in my mind, something somber and turbid; I felt other teachers were talking to me from behind a screen, as if they were far away, though they could reach out and touch me. I tried to convince myself that the somber spirit was created by mistake, by confusion, by a misunderstanding that would be resolved soon. Maybe the principal hadn’t seen the test scores: surely when he saw them everything would change, return to its normal course, and there would be no need for a new grammar teacher. But beneath this dismal spirit I could see the red, shiny sandals, the tight flattering skirt with a slit on the right side, the hair bobbing from side to side, and the eyes staring aloofly at the principal and me.

When I told my mother about all this she shook her head in desperation. I waited for the right moment, and only when the two of us were alone in the kitchen did I tell her about the new teacher, so that my father and Matan wouldn’t hear about it. She followed every word, took interest in every detail, like someone who had predicted a terrible disaster and now wants to find out how exactly it came to be. I tried to describe the new teacher, but the details seemed insignificant, irrelevant. No, she is not exceptionally beautiful, though she is very feminine, but something about her appearance is too erect and stiff. I am positive there isn’t a trace of hubbub in her class: I suppose she intimidates the students with her low, quiet voice, without saying anything explicitly dominating. When Matan and my father entered the kitchen we became silent. They felt a conversation was interrupted and tried to inquire what it was about, but my mother looked down and began washing the dishes, while I left the kitchen immediately.

At the beginning of the week, as I entered the classroom and placed my books on the desk, the door opened and the principal and the new teacher appeared once again. Wearing a tight dress with a floral print design and the red sandals, she smiled at the students, and stood right next to me. I was horror-struck; the notebook I was holding dropped to the floor, the pen rolled on the desk and stopped at the very corner, right before falling down. I bent to pick up the notebook but in my confusion bumped my head into the corner of the desk. I felt my face flushing, my hands shivering slightly, and for a moment I thought I would burst into tears. But then I told myself I was behaving like a silly child, surely there is a perfectly acceptable explanation for her standing next to me, in a moment the humiliation will turn out to be a mistake, an error that will be rectified immediately.

But the principal looked indifferently at me with a straight face, a vibrating chin and quiet, practical eyes—he stood before the class, waiting for silence. He began by saying that a new grammar teacher was coming to our school, a talented, successful teacher whom we are fortunate to have with us, and she will teach this lesson instead of the permanent teacher. He didn’t say my name, only called me the ‘permanent teacher’. He was asking the students to behave well and assist the new teacher to become part of our school. After these short sentences he left the class in haste.

A girl sitting in the first row is watching me with pity. I freeze, I don’t know if I should step aside and leave or stay and watch her teach. My expression may resemble a smile, but my body is motionless and disobeys me, refusing to go away, yet unable to claim its place. As I am stretching a hesitant hand and leaning on the desk, the new teacher steps forward then stands facing the first row of desks. Her body is peaceful and tall, she doesn’t straighten her shirt or push a lock of hair to its place, but turns to the students and in a low, quiet voice she says that in this lesson we will talk about a new subject that hasn’t been taught so far, the analysis of complex sentences. For a single moment I become the student I used to be. I want to raise my hand and say that this subject is not a part of this year’s curriculum; immediately I understand how pointless and futile these words would be. In small, hesitant steps, looking neither at the students nor at the new teacher, I walk toward the door and exit the class.

I walked through the corridors as if I were blind, oblivious of where the walls are and whether I should turn left or right. A student who passed by said something, but I heard nothing but noise. I reached the teachers’ room, drew my handbag out of the small locker, opened it and looked for my purse and the keys, though no one had ever touched them, and when I found them I closed the locker, took my handbag and walked in a strange, disjointed way out of the school, without letting anyone know that I was leaving or asking someone to substitute for me in the next classes. After a strained walk of about half an hour, I found myself at the entrance to my parents’ home.

My mother, who opened the door, looked at me in silence and made an inviting gesture with her hand. Even before I told her what had happened tears began running down my cheeks, and she wiped them quickly with a folded tissue. The principal, the new teacher, the red sandals, the notebook that fell down and the way my head had bumped into the desk, they all accumulated to form a pile of discontents, yet their order was unclear and it was impossible to tell which one preceded the other; eventually they amalgamated into a future disaster from which there could be no escape.

My mother listened to me mutely, asking nothing, only nodding as if she was familiar with the story but wanted to make sure that I was recounting it correctly and that the details were accurate. Finally I was silent, and she kept shaking her head from one side to the other, like a person who knows a calamity is looming and cannot be avoided. So we sat together in silence. She kept nodding her head and making a small sigh once in a while and I stared at the embroidered tablecloth, my tears dried and my face red and swollen. Finally she said that maybe I would be able to find a job as a grammar teacher in another school.

A terrible rage took over me, an anger that spread and became physically painful. I felt as if an animal was running in panic within my body, unable to find its way out. I almost grabbed the vase from the table and tossed it against the wall. Again I pictured the new teacher and the principal, and then I looked at my mother: she should have cried out, come to my defense, struggled with the new teacher, and instead she lowered her gaze, yielding, suggesting that I escape before the iron school gate would slam behind me. All the good manners are gone, a daughter’s respect for her mother, it’s all over. I began shouting, accusing her of encouraging me to give up and not to struggle, she should have been there for me, who knows, maybe she even thinks the new teacher is really better than me. I stood there screaming, making ridiculous, preposterous accusations, arguing that she never appreciated me, complaining she thinks Matan is more gifted than I am, reminding her how my father knows the names of every employee at Matan’s workplace but he never asked what the teachers are called; finally I even said that perhaps she prefers that I fail, it would be easier this way. She sat there looking at me, neither replying nor denying, in her eyes a new, unfamiliar tinge of despair. As I turned to the door it crossed my mind that I had never noticed that she is a bit hump-backed. I pushed the thought away and left my parents’ place, slamming the door behind me, ignoring the welcome of a neighbor, and bursting into the street, full of red sunshine.

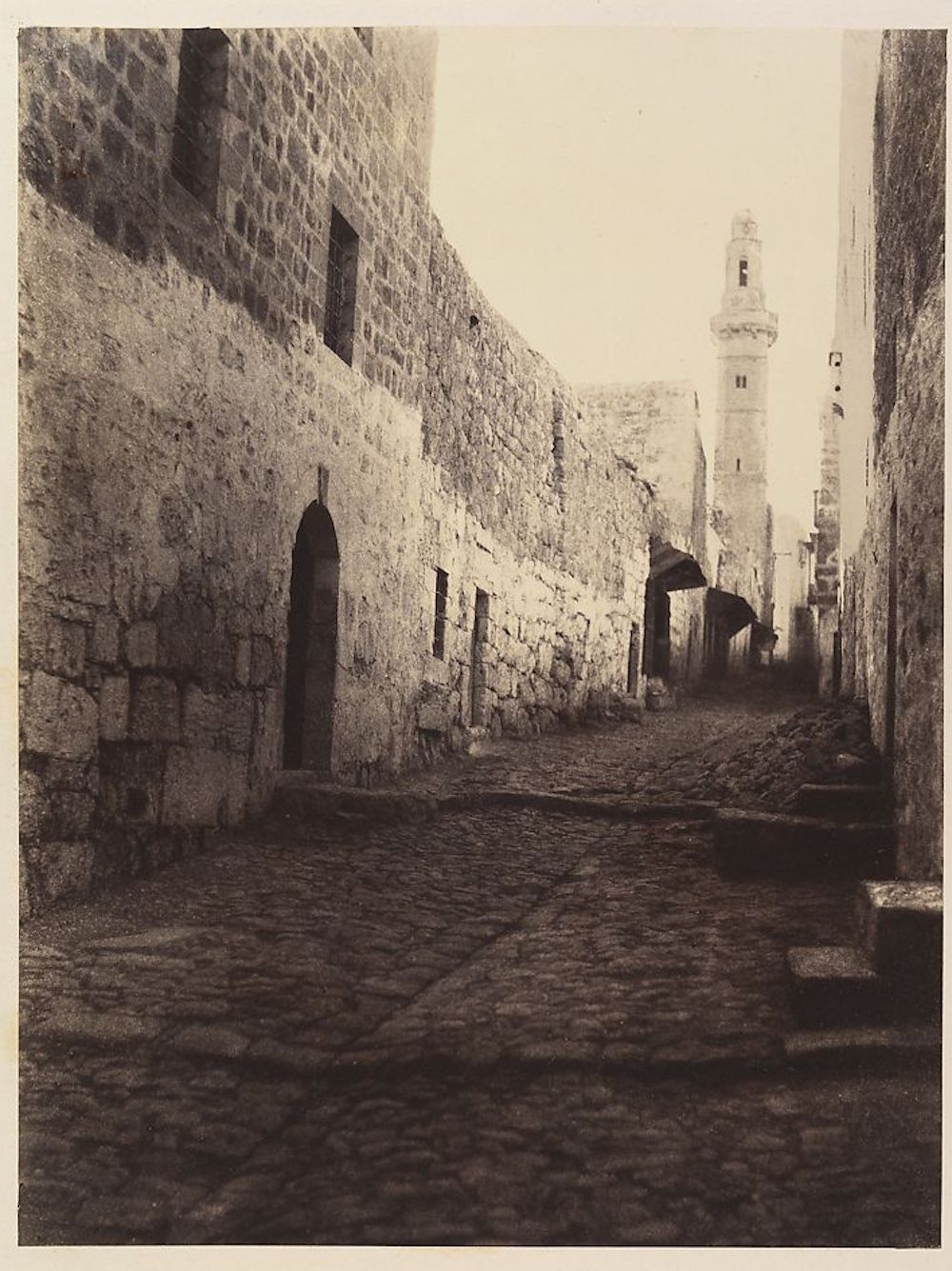

I don’t know how long I walked. I saw nothing but dusty pavements, the white stripes of zebra crossings, feet in shoes walking next to me. Every now and then I bypassed pits and other obstacles, once I almost slipped and fell but I grabbed an iron rail and kept walking. In one alley an old woman with a dark scarf on her head said something to me, but I didn’t understand her; I nodded and kept walking. Only when I felt exhausted and couldn’t walk anymore did I realize I was not far from my own place. After a couple of minutes I climbed up the stairs and drew out the keys; then the door opened and Matan stretched his arms towards me and embraced me.

First I cried, the teacher, the principal, the desk, the sandals, they were all transformed into one, long whine. My nose running, my hair disheveled, my eyes full with tears, I told him everything. Matan again embraced me warmly, wiped my tears with his fingers and said we must calculate our next steps. When I went into the kitchen I saw a fresh salad in a nice bowl, sweet-smelling, freshly baked bread, various cheeses: he had prepared dinner for the both of us. Moved and excited I sat down, and he put food in my plate.

While I began to eat he was thinking out loud. My mother had called him and told him what happened today. He simply couldn’t figure out why the principal wants to hire a new teacher, I have such an excellent record, one only has to take a brief look at the national test scores to see it. And why this teacher in particular? Is he acquainted with her? Perhaps they worked together somewhere, perhaps there is even a romantic issue here. My mother said she is too elegant, and completely unafraid of him—in fact it is the other way around, it seems that he is the one who is scared of her. Matan kept talking, determined to reach an accurate description of the teacher though he had never seen her, but I felt his depiction of the unfolding of events had a hidden purpose. He emphasized again and again the tight dress, the somewhat vulgar sandals, the brash, or at least extroverted, character, her apparent vanity, and even the complete silence in the class as she stood strong and erect facing the students. Finally, in a casual manner, he added that perhaps it would be wise of me to adopt some of these habits: clearly they would very useful to my career, and it could be argued that they are much more important than diligence and a continuous structured effort.

The walls of the kitchen turned vague, the delicate flowers on the tablecloth became blurred and the food residue on the plate blended into an obscure stain. I tried to comprehend Matan’s arguments but fatigue overtook me. For a moment I felt as if the entire kitchen was moving slowly. Matan saw my expression and said that perhaps I was not feeling well, I had such a hard day, I had walked for several hours, I had better lie down. He held my hand and I got up, went after him and relaxed on the bed. He took off my clothes, overcoming the obstacle of opening a button or a zipper as if it was a major task, and then he began to fondle me.

I am exhausted and Matan is absorbed in my curves, his hand seems heavy, and now I realize that he is crossing the boundaries, granting himself a new freedom, daring to touch me as if I were a stranger, as if we met in this room by chance and in a moment each one of us will go his own way. At first I try to protest, but weakness and pleasure prevent me from resisting him, and so we are caught in a whirlpool, both overpowering and illusive.

The next morning I decided to approach the principal directly. There was no point in being cautious, soon the new teacher would take my place. I put on a tight, straight skirt, tucked into it an ironed shirt; my face portrayed courage and even a hint of humor. When I got to school I turned immediately to the principal’s office. The secretary greeted me kindly. In a deep, husky voice she said hello and then asked how she could help me. She is very sorry, the principal is busy today, important appointments from early morning until late evening, could I tell her what it is about? No, of course, she understands. By the way, did I have a chance to meet the new grammar teacher? Amazing woman, isn’t she? So elegant, so talented, they say that as she enters the classroom the students are simply eager to study. We are so fortunate that she accepted the job offer at our school, it is teachers like her that make this school such a prestigious institution. In a moment she will ask the principal when he can meet me.

She stretched a rough hand, full of rings and with long red fingernails, to the phone and pushed an invisible button, whispering into the receiver and watching me; then she said in her hoarse voice that the principal hopes he will have time tomorrow. She will look for me at the teachers’ room and let me know when I can meet with him. As she saw the disappointment on my face she faked a smile, and promised that the appointment would indeed take place. I stood there in front of her embarrassed, as if I was a student reporting late for class, trying to convince the secretary that it wasn’t my fault, that circumstances beyond my control made me linger elsewhere. Before I left I said again that the appointment is very important for me, and she smiled and assured me that she would let me know as soon as possible when I could meet with the principal.

As I entered the class where the new teacher had replaced me I felt a certain laxity, as if a hidden, invisible stitch had been unraveled. The students didn’t hasten to sit down, a couple of boys kept talking even though I sat in my place, a kind of murmur was heard in the classroom, half-words, whispers, and a quiet giggling, even a long cough, which normally would stop abruptly as the teacher enters the class. As I got up the whispers decreased, but a buzz kept rolling through the class, vague and soft. When I turned to the board and began writing the subject of the lesson I heard behind me, loud and clear, laughter expanding in the classroom.

Already then, as I stood with my back to the students, I knew something had gone wrong and couldn’t be fixed; in an instant it hit me that all this gradual, constructed effort was in vain, a futile attempt to advance to a place no one wanted to reach. For a moment I saw the image of my mother, sad and modest, and immediately she disappeared and I heard the roaring, derisive laughter again. I should have ignored the noise coming from the class but habit made me turn around to the students.

Two boys sitting at the far end of the classroom next to the wall were laughing out loud, grabbing the desk and chair in a twitch, as if the laughter had been imposed on them. The other students looked at them and at me alternately, wondering what would happen now. In a loud, harsh voice I asked what was so funny. Something about my tone made one of them stop roaring. With a face full with tears he sputtered that his friend had told him a joke. Had he apologized, muttered something about being sorry, I would have gone on with class. But his provocative words, the amused voice, and the insinuating looks at his friend still choking with laughter made me furious; it was a rage I often saw in other teachers but I was inclined to dismiss it, to perceive it as evidence of weakness, perhaps even of laziness.

A cry startled the classroom. As I heard my voice it crossed my mind that it resembled a saw cutting rusty iron. Get out, I screamed, get out and don’t come back, there is no room for students like you in my class. The laughing boys were silent: apparently they had never suspected the quiet, polite teacher could shout like that. They both stood motionless, paralyzed by surprise, looking at me and wondering whether I might burst into laughter and all this would turn out to be a silly joke. The eyes of one of the boys were filled with tears, in a minute he would be crying; he leaned on the desk as if he was about to fall down, reclining his head and looking down at the floor, attempting to conceal the tears that began rolling slowly on the smooth cheek. Then his friend looked at him and said quietly: if he goes, so do I.

In a gesture of resolve I raised my hand and pointed at the door. I stood motionless, without dropping the hand, as the two of them stepped outside: both thin, one short and sloppy, the other with a slightly bent back. Only as the door was shut did I drop my hand and turn to the board. Even though I asked a couple of questions, no one replied. The silence oppressing the room was so heavy that even when the bell rang the students remained seated, while adolescent voices and brisk foot-tapping were heard from the corridor.

I collected my things and walked slowly to the teachers’ room. As I entered, my friend hurried towards me, grabbing my hand and pulling me as if someone was chasing us and we needed to escape.

I heard what happened in class, she whispered in my ear, these students are obnoxious; they should be expelled from school, so disrespectful, they think they can do anything, shameless, everyone is talking about it, they came crying to the teachers’ room and talked with one of the teachers, and she called the principal, and he spoke with them at length. Perhaps their parents will be called to school, I hope this time they will learn a lesson.

As I followed her, slowly other teachers began asking me what happened in class, with obvious excitement. I tried to explain – —the mocking laughter, the twitching, the degrading words about a joke, but it all sounded so foolish now, lacking the insolence of the roaring laughter, almost like a childish prick, something that would evoke, at most, a warning look.

As the teachers were surrounding me, repeating my words and interpreting every gesture, the secretary came in. Now she wasn’t smiling anymore; though her face was heavily made up and pink, clown-like circles were drawn on her two cheeks, her expression was as grave as could be. In her low, husky voice she muttered that the principal would see me the next day at ten o’clock, dropped a pile of papers on the table and left.

As the teachers around me were contemplating what I should say to the principal, one suggesting that I demand that the students be expelled, another saying they should be forgiven, I saw at the far end of the room the new teacher, sitting in the armchair, alert and probing and following the excitement around me. She sat erect, her bare legs crossed, wearing a dark dress and a golden necklace, her light hair swinging with the movement of the head, and her eyes watching me with a mixture of curiosity and contempt. I closed my eyes for a moment; then I tossed my books and notebooks into my handbag, said goodbye to the teachers and left school almost in a run.

Sky frightfully bright, sunlight nauseatingly blinding, wind carrying dust from a remote desert; I walked slowly, dragging my feet aimlessly only to be able to endure the distress spreading within me, threatening to become a huge growth that might suffocate me. One step after the other, the tears pouring down my face, my entire body struggling not to fall down and collapse.

I hear the cellphone ringing in my purse but I don’t answer. The streets of the city change, first I walk in broad avenues under the wide leafs of palm trees, then the streets fill with small fabric stores, furniture and house decoration shops, and finally I think I am in poorer quarters. My feet ache, I hurry to a bench in a small park and relax onto it as if it was a comfortable armchair. Then I realize the cellphone keeps ringing. Matan is looking for me. Someone called from school and said I didn’t attend class, they don’t know where I am. He is very busy with work now but distracted by his concern. Am I out of my mind, to disappear like that? Where am I? He will come to pick me up immediately. I don’t know in what street? What is wrong with me? Here, the name of the street is written. I will sit still, I won’t move from the bench; he will be there in a couple of minutes.

When we got home I lay motionless on the black sofa. Matan kept asking what had happened in school; though I did try, I was unable to tell him anything. The words didn’t add up to full sentences, the grammar was faulty, instead of saying ‘school’ I kept saying ‘synagogue’, and when trying to depict the secretary threatening me with an appointment with the principal tomorrow, I had to repeat the description several times since it was impossible to tell whether she had approached me or I was the one who asked for the appointment. I wanted to describe the teachers surrounding me and the new teacher gazing arrogantly at me from a distance, but all I could say was that I have no more strength, I can’t fend off the people around me anymore, and that I am tired to death.

I woke up after two hours. As I opened my eyes I knew a vague danger was slowly materializing but I couldn’t remember what it was. The anguish remained, as oppressive as ever, but lacking a distinct shape. Something ceased to be what it was, it was broken and could never be mended, but what was it? Murmuring voices emerged from the kitchen; I heard my parents and Matan whispering. Only when I heard them repeat the word Principal did I recall everything. The events of the day unfolded in my mind, the wild laughter, the weeping students, the teachers whose tranquility had been disturbed, and the secretary threatening me that tomorrow morning the principal would see me.

I got up from bed and walked to the kitchen. My parents and Matan sat around the table. As I entered they seated me on a chair as if I was sick, and my mother placed a cup of tea in front of me. They stood around me, their faces revealing concern and devotion, watching me and wondering how to start a conversation. Finally my father cleared his throat, caressed me lightly, and said he had heard that something happened again in school, apparently it was very serious, otherwise it would be inconceivable that I should leave school without saying a word, and it was practically impossible that I forgot a class was scheduled. Something about his tone made me feel resentful, he spoke to me as if I was a naughty child: you don’t want to shout at her but she shouldn’t be allowed to carry on with her tricks, she should be addressed softly but told very clearly that order and discipline must be kept. But in spite of the anger I managed to tell them, slowly and in sequence, all that had happened that day in school. When I was done they remained silent, immersed in their thoughts.

My father sat next to me, running his bony hands through his hair out of habit; he was wearing a ribbed shirt with brown and blue stripes, faded and old-fashioned, with a detergent odor. I saw he wasn’t sure what he should say. Finally, in his deep voice, he said that sometimes people don’t understand properly what is going on at the workplace, and this is particularly true for those growing up in a warm, supportive environment, among loving family members; they are unfamiliar with a strict approach and they tend to interpret any blunt word as an insult. However, I have to understand—now he was looking at me directly—the students are indeed rude but it is impossible to walk away during school hours. In spite of the vulgarity, the lack of discipline, the teacher should set an example for the others. He understands my agitation but I was wrong. He is positive that this is exactly what the principal will say when I see him tomorrow.

My mother looked at him. For a moment a hint of a smile appeared on her sad face and then it evaporated. She sat next to me and caressed me, her hand touching my hair, my face, my arm. It was her silence, fondling me but saying nothing, that brought me to tears. It’s all lost, this is what she is thinking, the new teacher will take my place and there is no way to reverse the verdict. Nothing can beat the tall, erect posture, the arrogant look, the hair swinging forward and backward with the movement of the head, the red sandals, not even absolute success in the national tests. I had better leave as soon as possible, before being expelled shamefully.

Matan said nothing. But in the evening, when we were alone at home, he began explaining what should be done, speaking rapidly, without breathing between the sentences, every observation creating a new concern. It would be wise to meet with the principal but it might make things worse, if I don’t present my achievements maybe the principal won’t take them into account, but clearly he is aware of the test scores, but if he knows, why did he hire the new teacher? She may be a good teacher, and clearly her appearance is an advantage, but doesn’t the principal want his school to do well in the national tests? Obviously he does, so how can he even consider replacing me with another teacher? The thread of thought was tangled, twisted and curved, sometimes disappearing and then emerging at an unexpected place, becoming a dense, matted skein, a knot that couldn’t be unsnarled, and all of Matan’s attempts to grab an end of the thread and untie it were bitter and insulting.

Late at night Matan hugs me, kisses my forehead, and fondles my hair. His face reveals his pain. He creases his eyebrows; I can feel his disturbed look even though his eyes are closed. I also shut my eyes, lying covered and motionless in bed, and then I feel his hand, crossing the limits again, dominating me, perhaps even with a touch of aggression. I open my eyes and look at him. Strange, but there is a sparkle of joy in his eyes, a glimpse of victory, sorrow mixed with provocation. He is not afraid that I will refuse, that I will avoid his body, acting as if he can do with me whatever he wishes, careful not to hurt me but fully absorbed by his pleasure. Enough, Matan, I push him away, leave me alone. He is looking at me with surprise, as if he has just found out that I am there, withdrawing slowly, turning his back to me, and after a couple of minutes I hear a slow, steady breathing.

The next morning I pushed the closet doors wide open and examined the dresses: one was white with tiny flowers scattered on it, a light summer dress that I had bought in a moment of weakness a day after I met Matan. Another one was brown with a narrow cut, I purchased it for a friend’s wedding but it was left untouched in the closet. There was also a blue dress with buttons, not too light and not too elegant; it glided easily onto my body. The high-heeled pumps were painful, my feet felt contorted, as though in a splint, but I paced slowly to the mirror and put mauve lipstick on my lips.

When Matan saw me he was speechless. His eyes were wide open, I couldn’t tell if it was lust or disgust. His expression, like that of a boy watching a magic show who can’t believe what he sees, made me smile. Then he got a grip on himself and muttered: are you out of your mind?

At exactly ten o’clock I got to school and turned to the principal’s office. The secretary examined me head to toe, faking a smiling without concealing her contempt, and then she said in her deep husky voice that the principal is still busy; please be seated in the waiting hall, she will call me when he is available. After a couple of minutes she pointed her colored finger, suggesting I should enter his office. The principal was immersed in writing. Without diverting his look, he mumbled between his teeth sit down.

I sat on a brown armchair, my heart pounding and I hardly breathed, repeating to myself the speech I had prepared at home: I would open with an apology, perhaps hint that I wasn’t feeling well, and then immediately elaborate on my various achievements, without modesty, and refer in detail to the national tests scores. I had better not say anything about the new teacher, it would make me look petty, I should focus on my own advantages. This speech, which I memorized carefully all the way to school, now turned nebulous, parts of it disappeared. I couldn’t extricate them, and the words were stored in my memory without any logical sequence. But as I was trying to reconstruct it, to gather the various parts into a whole, the principal raised his eyes and looked at me.

A horrible smile, mean and mocking, spread in an instant across his face. Even though his big dark eyes remained frigid under his black thick eyebrows, a wide smile emerged on half of his face, revealing perfectly straight and identical teeth, almost as if they were machine-made; the other side of the mouth was inclined downwards. A scornful snort followed this twitch, like an engine’s blowing, a roaring that had it not immediately followed a smile one would have thought revealed resentment, or even anger. Exactly as the smile appeared in an instant, so it died in a split second, disappearing without a trace. Only the dark eyes watched me with concentration, and an irksome silence spread through the room.

I felt my back wet, my fingers were stuck on the sides of the armchair and my feet were painfully deformed in my pumps. I thought I heard bells ringing, something like a whistle, a rising and descending voice, like a screen with a low voice emerging from behind it, you can’t walk away whenever you feel like it, you have a responsibility to the students, what kind of example are you setting, any one of them might think that he or she can skip school whenever they feel like it, if a student behaved this way she would be severely punished, and now I will have to consider what to do. In between the harsh words I suddenly saw my mother’s face: she was right, I should have left before being expelled in disgrace, but the memory of her submissive face made me angry.

I interrupted him. I apologized but I was unwell, perhaps the beginning of a ’flu, I wanted to call but I found it hard to talk, and when I got home I lay on the bed and couldn’t move. And in spite of all this I believe my achievements should be kept in mind. I described myself as if I was not present in the room: an endlessly devoted teacher, thorough and well-organized, and all these qualities had borne such beautiful fruits, as my students got the highest scores in the country.

Where did it all go wrong, turn twisted and broken? Where was the flaw that distorted and falsified the path of the righteous, making it a damaged road, full of obstacles? Had I been blind to the warning signs, ominous signals that all that appeared reasonable and clear was leading to a huge crater, visible only when standing at its brink? The principal’s words echoed in the room, one word after the other, a description of errors and faults adding up to a detailed, well-reasoned verdict.

The problem is not that I left without any notice, though that is a severe violation of the regulations, but the way I conduct the lessons. My presence as a teacher is not strong enough, not to say deficient. The students feel no one is instructing them, the teacher has to be a defining person, a kind of leader, he is not afraid to say it, a charismatic personality. Though I teach well and I make sure that the students understand the material and prepare homework, this is not enough, memorizing and precision are not the heart of the teaching profession. Look at the new teacher, for example, she could set a good example for me. When she enters the classroom silence immediately prevails; the point is that the students are not afraid of her. She is both determined and relaxed, confident in her talent, and therefore the young adolescents follow her enthusiastically. And not that she is careless of the teaching itself, on the contrary, she is very meticulous, but her main advantage lies in an appropriate posture facing the class, the assertive and decisive spirit in which she directs the lesson. And by the way, yesterday she was appointed head of the grammar teaching in our school. Therefore I must meet with her so she can explain in detail what I should be teaching this year. And since lately I tend to disappear without notice, from now on I will have to report to her every time I arrive at or leave the school.

When I left the office I saw my image reflected in the wide, vitrine-like glass windows facing the principal’s office: a young woman, slightly bent, limping in her twisted high-heeled shoes, her dress missing a button and a white, stained tank top poking out of it. Her hair is disheveled, the red color that covered her lips in now smeared on her chin, and her eyes are wide open, as if she was walking in darkness. One of my students passed by me; she almost greeted me but when she saw me she screamed and walked away in panic.

The ringing bell echoes in the corridors. Boys and girls are running past me, rushing to class, stampeding in a mixture of laughter and alarm, once in a while bumping into each other, giggling and swearing, and only as they see me does the stream split, and they run to either side of me, watching me with amazement and horror as I limp slowly, looking down at the ground. Finally I reach the gate and leave the school.

As I stand on the pavement I take off my shoes and walk barefoot to the bus stop. My feet are wounded; I see the scratches yet I feel nothing. The bus stop is empty, but in a couple of minute several people come, standing one behind the other. I am second in the queue. Before me is a tall man, I see his sweating back. A few women arrive, speaking in whispers. After several minutes a packed bus approaches the stop. The line advances towards the entrance door, which opens with a bang, in perfect order, but then the woman who is behind me jumps the queue and hurries to the open door, and all the other passengers follow her. If it had still been morning and I on my way to school I would have said something about the need to wait in a queue, and I would probably have added, with a smile, a couple of words about people who lack decent habits and should return to school to learn some discipline. But now I stand motionless, pushed away by a woman with shopping bags, by an elderly man with a walking stick; a teenager with headsets moving his head to the rhythm of the music hits me with his elbow, the whispering women touch me lightly and get on the bus, and after them comes a slightly dirty man with strong alcoholic breath; he bumps into me heavily and pushes me, I trip and fall down. As I raise my eyes from the pavement I see that they are all on the bus, the doors are silently closed, then the bus growls and disappears.

I am sitting on a bench. I am not sure where I am, my cell phone is right next to me. A couple of moments ago I pushed one of its buttons because it cried out and trembled for a while; Matan’s voice came out of it, he was speaking constantly, neither stopping nor waiting for a response. I heard the word fired several times, something about the money that we need, again and again he was screaming that I should consider my moves. As his voice broke and he said he was sorry I pushed the button again, and the phone was silent. I tossed it into my bag and began to walk.

I am staggering along a long, narrow street. The sun is burning, drops of sweat roll down my back. The faces I see around me are somewhat blurred, perhaps because I am so thirsty. I look at the shop windows: elegant clothes, sweets in endless shapes, colorful ladies’ lingerie. A toy shop attracts my attention. I don’t know why but I enter the store. As I walk in I halt, astonished, standing with my mouth wide open in front of an endless variety of colorful trains, tiny cars, strange figures, half-man half-machine, building blocks in all tones combined in ways I have never seen before. I stand still, staring at every corner of the store, and then I see the dolls’ shelves. I hasten to them like a little girl, watching them yearningly. They look like beautiful toddlers, their big eyes open with amazement, their pink cheeks rounded, and their tiny mouths slightly open, perhaps smiling, perhaps revealing adoration. For one moment the envelope of primeval, boundless darkness surrounding me is slightly ruptured. Here is a beautiful doll, her light hair glides on her neck, she is wearing a glossy purple dress. I stretch out my hand and hold her.