The history of Zionism was written by men, no doubt. Its ethos is abundant with daring masculine pioneers and brave soldiers sacrificing their lives for the Jewish state. Also, the prevailing notion of a strong, self-defending ‘new Jew’ was closer to the popular perception of masculinity, making the aggrandizement of heroic men almost natural. But some women played a substantial role in the development of Jewish life in Palestine, later Israel. Unfortunately, they were deprived of their proper place in history books, in the past and also today.

One cannot overestimate the importance of the Kibbutz, the collective settlement traditionally based on agriculture, in the history of Zionism – an idea initiated and exercised for the first time by Manya Shochat (1880-1961). Born in Grodno, part of the Russian Empire, she was the eighth daughter of ten children. Her grandfather was one of Napoleon’s soldiers who remained in Russia, converted to Judaism and married a Jewish woman. They were secular middle-class Jews, but their son, Manya’s beloved father, became an orthodox Jew, creating an open rift with his parents. Like other family members he was prone to depression and suicide. His parents tried to prevent his turn to religion, but gave up after he tried to take his life.

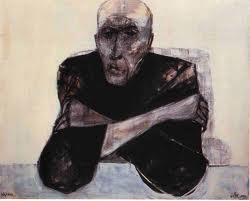

Manya’s character could be described as a blend of depression and suicidal inclination with a tendency to act in imaginative, unconventional ways. Already as a child her uncontrolled moods made attending school impossible. As a teenager she escaped home and, wearing men’s clothes, found a position as a porter. She later became a carpenter in her brother’s factory, a profession from which women were completely excluded in those times. Manya was deeply touched by the suffering and poverty of the workers around her and fully adopted socialist ideals. She joined the Bund, a Jewish revolutionist socialist movement, and later founded a Jewish Labor Party, which collapsed in 1903. Broken-hearted and depressed, she accepted her brother’s invitation to visit Palestine.

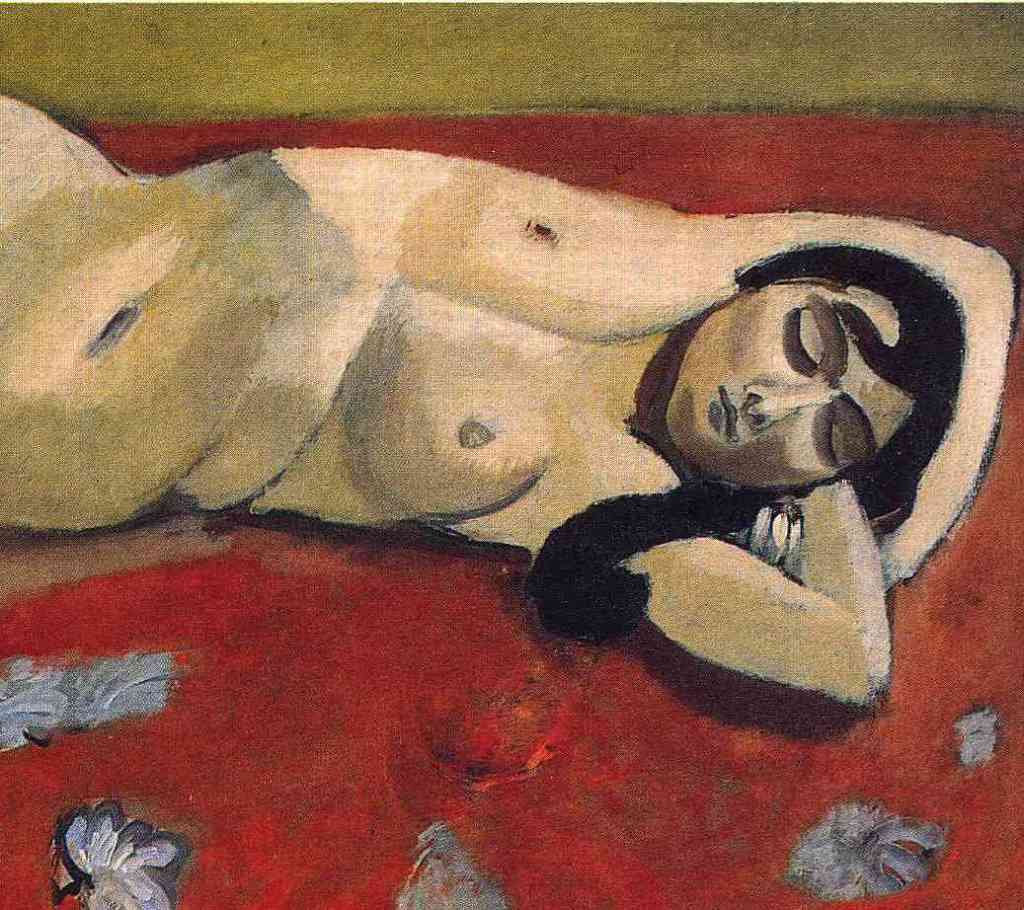

Like other pioneers before her, Manya fell in love with the land. She joined her brother in a tour looking for water and minerals, riding a horse from the Galilee to Jerusalem, to the Judea desert, and then to the south. The journey of the brother and sister, with two friends, lasted weeks. Manya cut her hair short; the two women dressed like men. She later said it was difficult to ride a horse with a long dress, but no doubt her appearance betrayed resentment against feminine embellishment. It illustrates well the nature of socialist feminism – focused on the social and economic oppression of women, and not on feminine identity and self-perception. Manya wished to work like a man and wear men’s clothes. Only once, as a child, did she want a velvet dress, but she was too embarrassed to ask for it.

The journey in Palestine pulled her out of her depression and she decided to stay, giving up her hope to be part of the socialist revolution in Russia. She wished to implant socialist ideas in the future Israel. Yet some Zionist pioneers already living in Palestine saw her as an imbalanced – not to say deranged – woman, with bizarre ideas of equality between people. But she didn’t give up her well-defined plans. In 1908 she was the one to initiate the first experimental collective farm in Sejera, in the Galilee, on land purchased by Edmond de Rothschild. This collective community was, in fact, the first Kibbutz – a unique way of life that made a substantial contribution to Israeli society.

Manya married Israel Shochat, a handsome man and one of the founders of the first Jewish military organization. Together they ran Sejera. Within a couple of months the collective community had eighteen members, six of whom were women, wearing pants and working in the fields with a pistol tied to their belt. There was something of a fraternity about this group of young people: the common jokes, a spirit of non-conformism, physical and mental strength, a profound knowledge of agriculture. Together Manya and Israel set the major principles of Israeli society in its first decades: military self-defense and socialist communities.

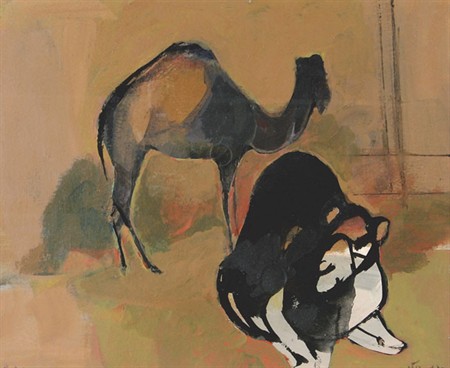

Manya was not oblivious to the Arab-Jewish conflict; her attitude towards the Arab communities was ambivalent. As a socialist, she was eager to advance social unions among the Arab population. As a Zionist she couldn’t help but admit the conflict of interest between the Jewish pioneers and Arab villagers and Bedouins. Yet she often demonstrated her fascination for the local Arabs – conducting long conversations whenever possible, paying them visits, and even attempting to adopt their daily habits.

With the foundation of the State of Israel, other leaders replaced Manya and Israel. She joined another kibbutz; he moved to Tel Aviv, leaving her with two children. Her son, a pilot in the RAF and one of the founders of the Israeli Air Force, committed suicide in 1967. Her daughter lived in Australia. But Manya, in spite of her suffering, remained unchanged: struggling with depression, finding solace in decisive action, and always looking for innovative ways to create a better society.