The “working class” is a term we tend to associate with the Marxism and socialism of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Although it was already in use in the Middle Ages and during the Industrial Revolution, when we think of the weaker segments of society making a living from manual labor, poor people whose rights are sometimes entirely neglected, it seems that only in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries they got the attention they deserved. But a change in social attitudes is almost always the result of a long and latent process, sometimes lasting decades and even centuries.

The Spanish painter, Diego Velasquez (1599-1660), was a man ahead of his time in many ways. Opposing the spirit of the Spanish Inquisition, he painted the human body realistically and nude, as did his Italian contemporaries. He was an individualist, an innovator, describing how reality can be reflected in endless ways; when his work was discovered in England in the nineteenth century, students of art were astonished: it turned out that what they considered to be modern and innovative existed in Spain two hundred years before.

“Christ in the House of Martha and Mary,” painted in 1618, depicts a story from the New Testament (Luke 10:38-41). While traveling, Christ stops at a village. A woman called Martha invites him to her house. Mary, her sister, sits at his feet and listens to him speak. Martha complains that Mary doesn’t help her prepare the food, to which Christ answers, “Martha, Martha, you are worried and upset about many things, but only one thing is needed. Mary has chosen what is better, and it will not be taken away from her.”

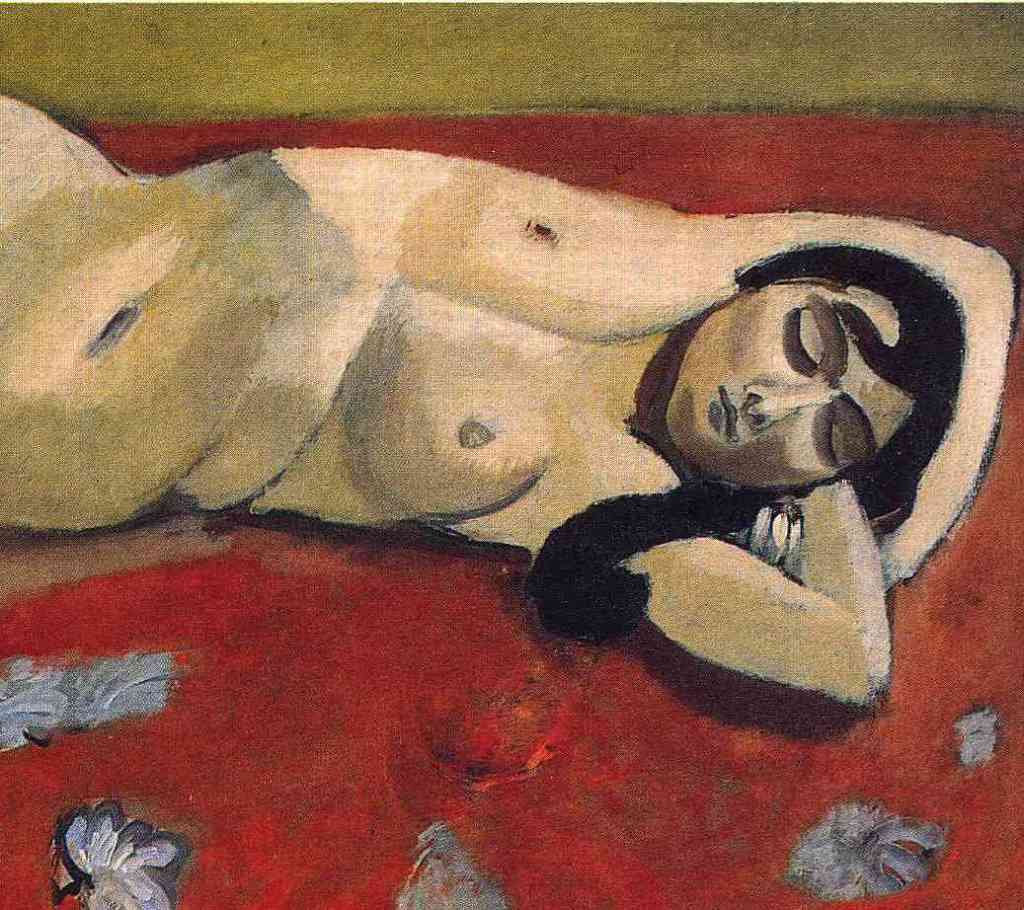

The painting is composed of two parts: a scene in the foreground and a small scene in the background. The manner in which Velasquez integrated various images in his art has been studied extensively by art historians. In this painting, they debated whether the small scene in the background is a picture hung on the wall, a mirror, or the second part of a simultaneous depiction of two scenes. It would suffice to say that most scholars agree that the smaller picture is a description of the biblical scene, and the bigger one is Velasquez’s interpretation of it. In the small picture we see Christ sitting on a chair, Mary is sitting at his feet, listening to him, and Martha stands behind her, complaining that she isn’t being helped. In the picture in the foreground, we see Martha, looking like a maid, after she has prepared dinner, wearing a bitter expression. She isn’t looking at the small picture but at the spectator. Her resentment is clear. An old woman stands behind her, probably lecturing her, reminding her of her duties.

Velasquez’s choice to depict these verses is interesting and compelling: Jesus, whose is always devoted to the meek and the needy, overlooks Martha’s hard work and sides with Mary. This scene was interpreted in many ways; the most prominent is that Mary had chosen the contemplative life and Martha the active life, which made Christ prefer Mary. But if we ignore these explanations and simply read the verses, there is something upsetting about this story: Christ is depicted as preferring the believers to the workers. The scene generated two types of people: one working and the other avoiding work due to spiritual engagement. Christ ridicules Martha, disregarding her claim that there is injustice, and thus legitimizes an unfair division of labor. It could be argued that the scene entails a hidden criticism of Christ. From a modern perspective, his stand certainly is intriguing and does not agree with his constant prominent inclination to do justice and act for the weaker members of society.

But Velasquez does more than simply depict this scene; he portrays very vividly Martha’s discontent. The major part of this painting focuses on Martha’s annoyance for having to prepare the food, set the table. She is a maid who has to work harder because Christ agreed that the preparation of the meal would not be divided between her and Mary. Martha looks like a hard-working young woman: with a ruddy face, blemished skin, and the hands of a manual worker, her appearance reveals no spirituality, only labor. She may be one of the earliest examples of the depiction of a “laborer” in the modern sense of the word: a person engaged in manual work, his or her description characterized by a sense of injustice. Not only did Christ refrain from helping her, the elderly lady behind her is preaching to her, telling her she should not be so bitter.

Many of Velasquez’ works depict biblical scenes, and it is generally assumed he was very religious. But this painting suggests this may have not been true. He may have been closer to the spirit of twentieth-century socialism than we assume. The clothes of the characters indicate they lived in different times. Martha seems like Velasquez’s contemporary, thus the painting can be interpreted as a cause and effect: Christianity generated inequality between people, religion created different classes (a working class and those who take advantage of it). Martha turns her gaze away from the biblical scene as not to see the Christian message, which she perceives as unjust.

It goes without saying that Velasquez, who lived in the seventeenth century, did not perceive the laborer as we do today. But this painting lays the foundation for the modern idea of a working class. First, it illustrates different classes; the maid is engaged in hard physical work, she complains that she has to work while others avoid work. Her rights are kept by neither Christ nor the elderly woman (who probably stands for popular wisdom). And, eventually, the worker has to do her job. In spite of her resentment, she doesn’t really have the power to revolt against social injustice—that would be fully and theoretically formulated hundreds of years later.