One cannot overstate the importance of the birth of Christ – the Western world was profoundly affected by Christianity, which ascribes the utmost religious importance to the birth of God’s son. Mary, as we all know, conceived though the power of the Holy Spirit and gave birth to Christ in spite of being a virgin. We could almost mistakenly say that this divine birth appears in various works of the art, but the truth is that the birth itself is never portrayed. We only ever see Mary holding the newborn baby in her lap. I’m wondering, was the birth painful? Long? How did Mary cope with the contractions? In spite of extensive discussions on this divine birth – its religious, philosophical and artistic meaning – we know almost nothing about how Mary herself experienced it. Western culture got used to deliberating on the birth of Christ without paying any attention to the actual birth, to the point that it seems natural to discuss the birth of who many believe is God without asking how his mother felt.

The experience of giving birth wasn’t always denied. In fact, at the heart of the Judea-Christian tradition lies a description of giving birth, in the story of Adam and Eve. After Eve made Adam eat the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge, God punished them and all humanity: “to the woman he said I will make you pain in childbearing very severe; with painful labor you will give birth to children … to Adam he said … by the sweat of your brown you will eat food until you return to the ground” (Genesis 3:16-19). And so, two related facts were implanted in western consciousness: the suffering of women at childbirth and the need to work to make a living. Some traditions that are the source for the Book of Genesis already existed in the tenth century B.C., and others came later – so for thousands of years, the western world internalized the pain of giving birth and accepted it as a fact to life, just like the need to work. To give birth is to experience a substantial torment; that’s the way of the world.

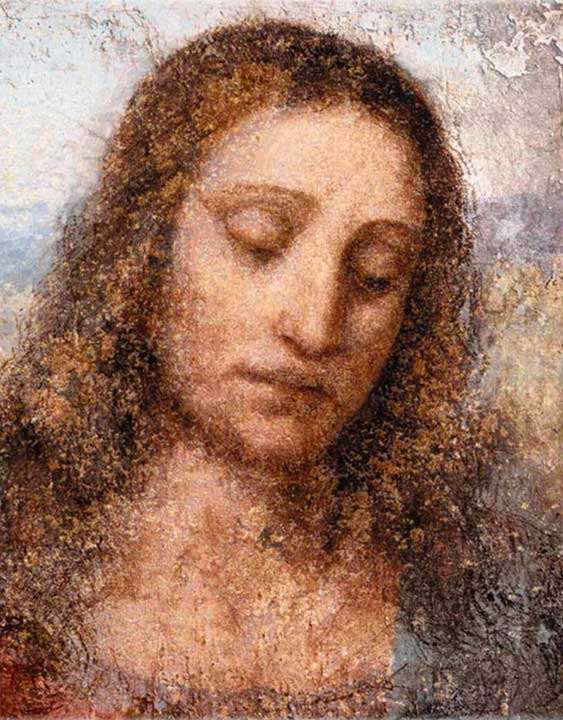

So why is there no depiction of Mary’s pains while delivering Christ? By the time Christianity was born, the pains of giving birth were self-evident. The image of the Madonna had dramatically changed the attitude towards the birth. Since she had given life to the Son of God, she herself had a unique nature, essentially different from any other woman. As she was impregnated by God and not by man, Mary was holy, a woman who—unlike any other human being—does not carry the burden of the Original Sin. And thus a belief had been created that her giving birth to Jesus was painless.

The New Testament provides two version of the holy birth. In Luke, it says “she gave birth to her firstborn, a son. She wrapped him in cloths and placed him in a manger, because there was no guest room available for them” (Luke 2:7). There are no anxieties, no contractions, no changing body – only giving birth, wrapping the baby, and putting him to sleep. Matthew’s version is different. “This is how the birth of Jesus the Messiah came about: His mother Mary was pledged to be married to Joseph, but before they came together, she was found to be pregnant through the Holy Spirit. Because Joseph her husband was faithful to the law, and yet did not want to expose her to public disgrace, he had in mind to divorce her quietly. But after he had considered this, an angel of the Lord appeared to him in a dream and said, “Joseph son of David, do not be afraid to take Mary home as your wife, because what is conceived in her is from the Holy Spirit. She will give birth to a son, and you are to give him the name Jesus, because he will save his people from their sins” (Matthew 1:18-21). Also here, there are no details of the physical process of giving birth.

But generations of Christian theologians developed the notion that since Christ’s birth was divine, it was painless. Christian thinkers dealt with almost any aspect of the Madonna (Mariology is the theological study of Mary) – but since the Gospels don’t provide any details of the birth, gradually a doctrine of the painless birth came into being. Eventually, the very lack of suffering became the proof of Mary being impregnated through the Holy Spirit.

There are various examples for this view. One well-known example is the protocols of the Roman Catholic Council of Trent, which took place in the sixteenth century. In this ecumenical council, the Roman Catholic Church rephrased its dogmas in the face of the growing Protestant movement. It promulgated a catechism which states “just as the rays of the sun penetrate without breaking or injuring in the least the solid substance of glass, so after a like but more exalted manner did Jesus Christ come forth from His mother’s womb without injury to her maternal virginity.” The Roman Catholic Church and the Orthodox Church held this view of the sacred birth. Protestants didn’t ascribe such theological important to Mary but have adopted her image as a virgin and a righteous person.

Thus, two ‘types’ of birth were implanted in the common consciousness: a divine one, which isn’t a result of a sin and isn’t a punishment, and is a painless birth; and a human negative birth, which is both a result of a sin and involves much suffering. There is a sublime birth, adorned, a ‘role birth’ in contemporary terminology, and a birth that is better forgotten because it is an agonizing divine torture.

Eventually, the Christian world completely repressed the simple feminine experience of giving birth – one that is painful but not because of a sin, it involves profound physical and emotional changes, and usually ends with profound joy. The mixture of accepting the pain of giving birth as a fact of life and ascribing such negative value to this suffering ended in an almost complete neglect of the normal feminine experience.

Examining modern literature reveals that the number of birth descriptions is almost negligible compared to any other meaningful human experience. If we look at how many books have been written on love, sex, divorce, sickness, or death, we would have to reach the conclusion that birth has been almost fully repressed. But since we are so used to not reading about giving birth, we casually accept this as normal without questioning. How is it possible that such a deep and meaningful experience is missing from all forms of art?

We might try to do some justice to Mary and imagine her giving birth in more human terms:

The air in the barn was thick, full of the smell of animals. She needed plenty of blankets, it is cold in Bethlehem at the end of December. The midwife was completely unaware of the special nature of this delivery, she boiled water at the far end of the barn to clean Mary during and after the birth. Like most first births, it was very long. Mary sank into despair and cried bitterly, begging for help. Hours of pain blurred the hopeful expectation; at certain moments she didn’t know what she was doing there. As Jesus’s head finally appeared, she knew the suffering was close to being over. Jesus was pulled out of her body and made a cry that resembled a bleat. The midwife placed him on her naked body, covered with fluids and still attached to the umbilical cord. Mary hugged him, thrilled as she saw his eyes open for a split second and then close again. As the midwife took him away, Mary leaned back, heaving a quiet sigh. Through a hole at the top of the barn, she could see stars in the sky, gleaming in an unusual light.