There is something elusive about the Middle Eastern landscape: a blazing sun creates vivid colors, yet the dusty air blurs the contours; desert sand makes the lively hues of rocks, bare hills, olive trees dull and faded. Many European artists have tried to capture the unique light and the peculiar landscape, often perceiving it as a sort of primordial scenery. So different from the European landscape, at times it seemed almost mystical, with its ravines, meandering hills, and arid vegetation.

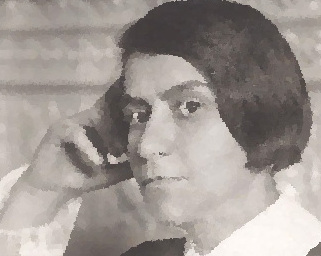

Anna Ticho (1894-1980) was an Israeli painter who devoted her life to depicting Jerusalem and the Judean Mountains. Born in Brno, then part of the Austro-Hungarian empire, her family moved to Vienna to enjoy its flourishing culture. Anna often visited the Albertina Museum, admiring the works of Durer and Bruegel. She took art classes and began to draw at the age of fourteen.

When she was eighteen years old, the Jewish organization “For Zion” sent her cousin Dr. Abraham Ticho, an ophthalmologist, to Palestine to open an eye clinic in Jerusalem. Anna decided to join him on his journey. The cousins fell in love and married.

When they arrived in 1912 Anna was in a state of shock. The views, the colors, the buildings, the people – everything was so different from anything she had ever seen. She was so overwhelmed by the new surroundings that she could not even express her feelings through art. For four years Anna made not a single painting.

As WWI broke, Dr. Ticho, a reserve officer in the Austrian army, was sent to Damascus, where he served as a surgeon. He couldn’t find a suitable nurse, so Anna volunteered to be his assistant, an occupation she continued until his death. As the war ended they returned to Jerusalem and purchased a beautiful house in the center of Jerusalem. The lower floor was an eye clinic where Dr. Ticho treated all sorts of patients – rich and poor, high officers of the British Mandate and Jewish immigrants, mainly from Germany – with his wife as his nurse.

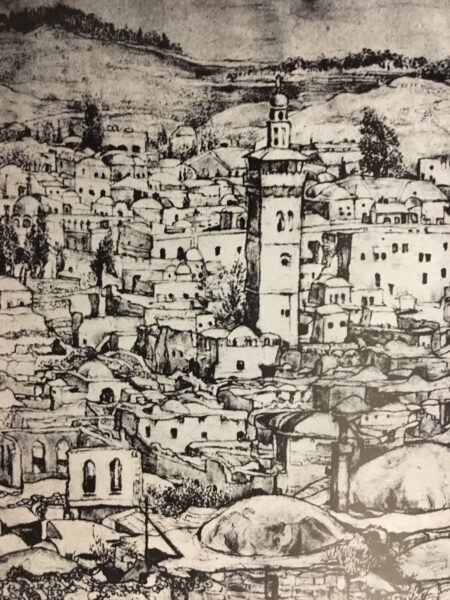

Now, after years in the Middle East, Anna had already grown accustomed to the strange country. She was completely fascinated by the landscape surrounding the city. On the edge of the desert, with buildings covered by Jerusalem stone, Anna walked for hours around the city, trying to capture the unique landscape in her drawings, mostly using nothing but a black pencil. Walking alone in uninhibited areas wasn’t safe, but she wouldn’t give it up. She fell in love with the surroundings. She dedicated her time to both assisting her husband and creating wonderful drawings. The influence of Durer is clearly reflected in her work from that time: delicate pencil drawings, detailed description of the landscape, very expressive. The hills of Jerusalem, people of very different origins, the exceptional light are all found in her drawings.

Unlike many Israeli artists of this time, Anna did not make any attempt to embellish the landscape or the city. Her art was utterly detached from any Zionist notions. She depicted stony ground, huge thorns, leafless trees, poor people, making no effort to adorn the bare land or soften its bleakness. At times her art seems almost religious – the views seem so primordial that they appear like some kind of pre-human land, almost divine. There is no reference to Jewish or Israeli themes, only a direct unmediated observation of nature.

In 1960 Dr. Ticho passed away, and Anna decided to leave their home and move to Motza, a neighborhood on the outskirts of Jerusalem, located on one of the hilltops of the Judean Mountains. The view was breathtaking, magnificent. But Anna, following her inner artistic drive, began to paint in her studio. No longer did she feel the need to see the landscape as she portrayed it – now she allowed her recollections to shape her art.

In the balance between a realistic depiction of concrete objects and a portrayal of an inner experience, the latter had the upper hand now. Anna began to use colors and to experiment with pastels to try and express her impression of the landscape. This withdrawal into the studio, reliance on past impressions, perhaps now more processed, generated wonderful paintings of the views around Jerusalem. Her art now lacked the almost mystic character of the past. It became softer, with greenery and flowers, perhaps revealing more affinity to the land.

Many immigrants coming to Israel have been overwhelmed by the landscape, so different from their natural environment; not taken aback by ideological barriers or the social obstacles, but simply unnerved by the foreign landscape. Anna, gifted artist that she was, depicted the very slow and sometimes painful process of adjusting to this new geographic region. First came shock and inertia, then an attempt to grasp the strange land through detailed observations, and finally, after containing it, an inner freedom to express both reservation and affection.